Clark Montgomery on blindness, technology, accessibility, and inclusion

Did you know that the first long-playing records (or LPs, as they are known) were not designed for music? Instead, they were used to record talking books for the blind. In the 1930s, the demand for talking books increased dramatically once soldiers returned home from the first world war. Many blinded veterans, unable to read Braille, needed another way to access literature and information.

The American Foundation for the Blind stepped in, licensing the technology and working with the Carnegie Corporation to develop the first modern LP, a 33 1/3 rpm vinyl disc. By 1942, the AFB had distributed over 23,000 “Talking Book machines,” according to their estimates. Eventually, record companies discovered how to make music sound as good as recorded voices on LPs, and record albums became household items across the nation.

I was introduced to this story by a client, Clark Montgomery, who reminded me of an important technological trend. Often, the development of new technology and accessibility features intended for a specific audience ultimately benefit everyone. One might even argue that the best examples of accessibility are those that are all-inclusive, enhancing the user experience at any level of ability.

Clark’s experience with sight loss and technology

Having been diagnosed legally blind over twenty-five years ago, Clark has had a wide range of experience with both assistive and mainstream technology over time, bearing witness to its usefulness from low tech to high tech advancements.

In the early 90s, when Clark was first suffering severe sight loss, he started using basic technologies including audio books on cassette and binoculars. The computer era was still in relative infancy at the time. Over the next several years, Clark would observe and benefit from an extraordinary burst in assistive technology, which he kept up with through his involvement with organizations in the field.

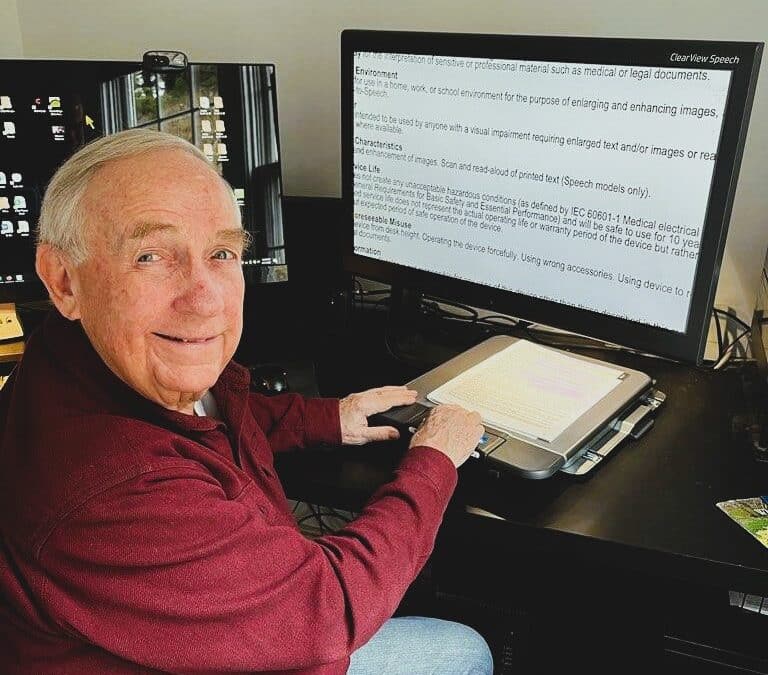

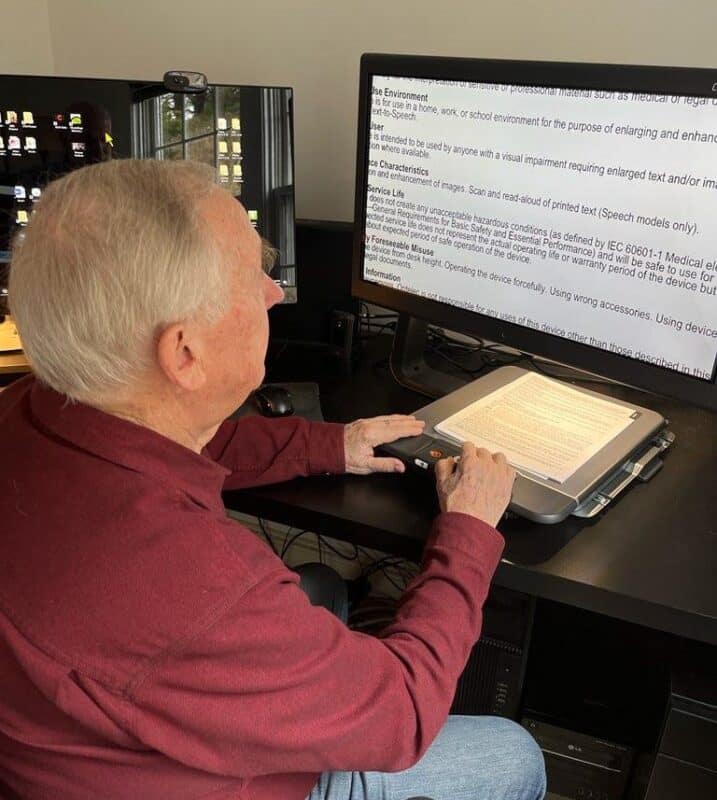

Today, Clark uses an Optelec ClearView C Speech, which he is highly enjoying. Though he been accustomed to using desktop video magnifiers since the mid-90s, the ClearView C is his first desktop magnifier with a touch screen and OCR text-to-speech capability. He has found the device especially helpful for a variety of tasks – reading, writing checks, and reviewing prescription labels, to name a few. Over the decades, desktop magnifiers have advanced from large, somewhat cumbersome CCTV viewers to more manageable and sleeker flatscreens with customizable settings, high-tech features (like OCR and touchscreens) and easily moveable trays for smooth reading. Clark believes that this type of magnifier is the most useful tool a person with low vision can own.

Clark using his Optelec ClearView C Speech.

Clark was also one of the first users of Zoomtext software. Blending assistive technology with mainstream, Clark uses Windows desktop PCs with 28” monitors and an accessible keyboard and mouse, taking advantage of screen magnification and text-to-speech for web browsing and other computer work. He also uses a smart speaker and an iPad Pro with native iOS accessibility features including magnification, VoiceOver, Speak Screen and Speech Controller. (For an overview of iOS accessibility features for users with visual impairments, refer to this guide from the American Foundation for the Blind.)

Features like “pinch-to-zoom,” once developed as an accessibility tool for low vision, are so common today in the world of touch screens and on-the-go web browsing. Once again, we see a tool originally intended for a narrow audience ultimately benefiting the larger community. A well-planned, inclusive design has staying power even as technology on the whole is constantly evolving.

The importance of education and awareness

Yet, Clark reminds us that many people, especially the older generation, are unaware of these types of features that could be very helpful to them. Friends in their eighties who have developed age-related macular degeneration often don’t know about the tools they likely have at their fingertips – namely, the accessibility settings on most every smartphone – and Clark does his best to persuade and educate those in his circle who would benefit.

Another challenge is access to hands-on learning. Facilities that offer a range of assistive technologies for people to try out can be a goldmine. People who live near these types of facilities should take advantage of them, not only to find the technology that can help, but also to stay apprised of new developments in the field. (We’ll include some ideas for how to find a facility near you at the end of this article.)

If traveling to see products in action is not feasible, Clark recommends checking out the wealth of videos that are available on YouTube, particularly product demonstrations. He learned about the ClearView C Speech through AdaptiVision’s video demo, and a quick YouTube search will result in thousands of other product demos and reviews by real users of assistive technology.

Overall, assistive technology helps people with vision loss or other disabilities lead productive lives, contributing and participating alongside their peers. Therefore, improving education and access to assistive technology for those who need it builds a more inclusive, accessible world for everyone.

Assistive technology and digital accessibility

According to Eamon McErlean (Forbes), “People who live with disabilities deserve to inhabit the same reality as those who don’t.” As far as digital accessibility is concerned, McErlean argues that genuine accessibility helps everyone, removing barriers to information, products, and services. Rather than considering accessibility after-the-fact or as an aside to core functionality, a platform (like a website or software program) should make accessibility features a priority. Digital access means everyone can get the information they need in the same way, whether or not they are aided by assistive technology – like a screen reader, for instance.

McEarlean uses a simple example to illustrate the point: a pair of scissors. Most are made for people who are right-handed. “Removing ‘handedness’ from things like scissors helps lefties and hinders no one,” McErlean asserts. The same concept can be applied to digital accessibility. Breaking down barriers for people with disabilities creates a more inclusive experience for all.

Using technology to help cope with sight loss

The unfortunate reality is that many people struggle with feeling isolated and excluded because of their sight loss. Clark empathizes with those facing the terrifying question, “am I going blind?” However, he reminds us that there are so many tools enabling people with vision loss to stay engaged, to enjoy life. Sight loss, according to Clark, will not be a crippling problem. Even relatively simple tools like a monocular or a lighted handheld magnifier can be extremely useful. The first step is to do the research, find out what’s available to you, and then put into action the tools that work. He also emphasizes the importance of relying on family members for help researching assistive technology and narrowing down options.

A human-first approach

Losing one’s sight is a traumatic experience, whether gradual or sudden. Family members and other support people can help. In my opinion, walking alongside those struggling with sight loss is yet another way we can work toward inclusion. Prioritizing the real needs of real people opens the doorway to accessibility. We should seize this opportunity in all areas of life. By putting people first, we will find long-term, innovative, and accessible solutions that are unifying and beneficial to all.

Further Resources

If you need help finding or researching assistive technology for low vision or blindness, please consider the following resources.

The American Foundation for the Blind offers a monthly online technology magazine edited and reported by experts who are blind or have low vision, plus a searchable listing of assistive technology and independent living products.

Vision Aware has a comprehensive directory searchable by category. You can search by state within the “Assistive Products” category to find relevant organizations in your area.

The American Council of the Blind maintains a list aids and devices and related organizations at various locations across the country.

Finally, you can find a range of low vision resource directories on the Living Well with Low Vision – Prevent Blindness site. Directories include assistive technology products, suppliers of low vision devices, and financial assistance, among others.

You may also wish to consult the Resource tab on our website, which includes a list of New England area resources in the categories of Equipment & Technology, Eye Care, Support Groups, Rehab Centers, and others, organized by state. AdaptiVision offers hands-on demonstrations at our Massachusetts demo room, plus virtual and in-home consultations.

If we can be helpful to you at any point in your research, please feel free to contact us.

Author Information

By Bethany Wyshak. Reviewed by Stuart Flom.

Sources

Early History. (n.d.). The American Foundation for the Blind. Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.afb.org/about-afb/history/online-museums/afb-talking-book-exhibit/early-history-why

Eveleth, R. (2013, April 29). The First LPs Weren’t for Music—They Were Audiobooks for the Blind. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/the-first-lps-werent-for-musicthey-were-audiobooks-for-the-blind-44381690/

McErlean, E. (2022, May 6). Make Space For All: Digital Accessibility Benefits Everyone. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/servicenow/2022/05/06/make-space-for-all-digital-accessibility-benefits-everyone/