Why Assistive Technology Matters to Me: Tom Pey, CEO, Waymap

We had the pleasure of speaking with Dr. Tom Pey, CEO and Founder of Waymap, about how Waymap technology is changing the way blind and visually impaired people navigate the world. As both a tech industry leader and someone who has personally confronted sight loss, Tom offers a unique perspective on why assistive technology, in particular navigational tech, matters to individuals with disabilities.

What exactly is Waymap?

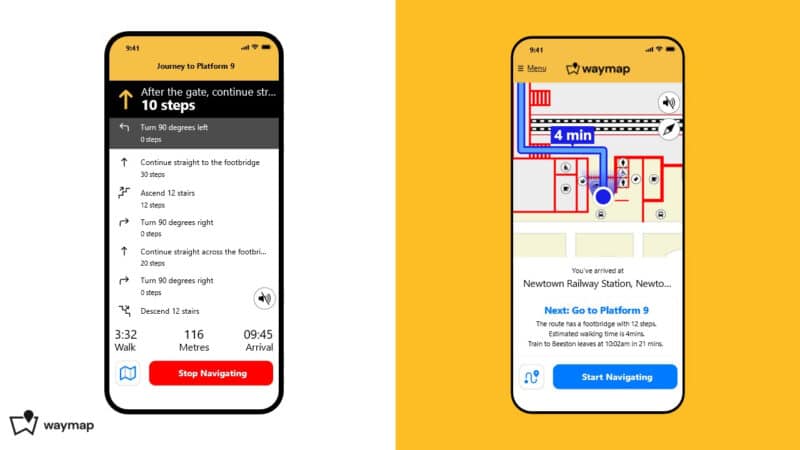

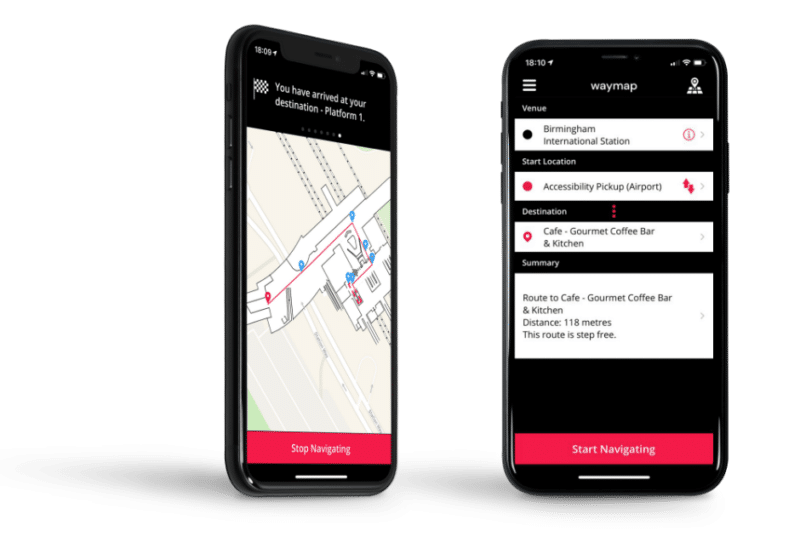

Waymap is a mobile application that provides turn-by-turn navigation to users. It does not require any Wifi or cell signal, so it works as well indoors and underground as outside. While Waymap was originally intended for blind and disabled travelers in urban environments, it’s built to take anyone anywhere.

Waymap’s navigation is accurate to within one meter and can recognize the direction the user is facing to within ten degrees. Users receive highly detailed, personalized, step-by-step audio directions, including the exact number of steps to take or degrees to turn. With such precision, the app can take you from, say, your front door to your office desk, or virtually any other destination. In Tom’s words, “We take you on a complete journey.”

The app has minimal battery load, which is especially advantageous on-the-go. Unlike other types of navigation apps, Waymap does not rely on the phone’s camera, so it won’t drain the battery and is, moreover, “heads up and hands free.” Individuals with disabilities can listen to audio directions while safely maneuvering a white cane, guide dog, or wheelchair.

How does it work?

Waymap’s algorithm uses built-in smartphone sensors together with maps, requiring zero additional infrastructure. Here is a short video explaining how Waymap works.

Waymap, Anyone Anywhere from Waymap on Vimeo.

One notable feature is Waymap’s ability to communicate real-time updates to users. Waymap takes public information, like train line service changes and elevator outages, and makes it accessible to users – even if they are underground.

On a deeper level, Waymap gives users the freedom of choice. For example, say you are riding the subway train in a wheelchair and encounter an elevator outage at your stop. You may feel a rising sense of anxiety, stuck in a crowded station trying to devise an exit plan. On the other hand, using Waymap, you would receive a message on your phone about the outage plus real-time reroutes, offering various solutions such as exiting at the next stop or transferring to another line. You would be empowered with the right information at the right time along with actionable solutions at your fingertips.

Users can even stop and ask the app to double-check their location. In this instance, the app will use the phone’s camera to locate you within 48 cm of where you are standing, providing timely reassurance to get you on your way.

As Tom describes, “You get to make choices and solve problems for your journey.” This freedom of choice, combined with the app’s trust-building navigational accuracy, helps users develop the confidence needed to travel independently.

Tom remembers well the frustrations of travel when he first became visually impaired: trying to memorize routes and getting lost quite often. Unfortunately for many people, vision problems can lead to less frequent trips out of the house and resultant feelings of isolation. Tom’s research has shown that blind individuals use on average just 2.5 routes regularly, perhaps getting them to the store, pharmacy, or bank. Otherwise, they are dependent on friends or family to help them get where they need to go. Waymap disrupts this pattern, offering a new way to travel that helps a person maintain his or her sense of control.

As Tom summarizes it:

“You get infinite solutions for the problems, given to you in a way that doesn’t take away your feeling of control as you’re moving around… We don’t see our job as taking over for the human brain. We just see it as aiding people to become much more independent in how they get around.”

— Tom Pey, CEO, Waymap

Tom’s personal experience with sight loss

Tom lost his sight rather suddenly at age 39, stemming from a childhood injury. He has documented the story in The Guardian (“Experience: I banged my head and went blind 30 years later”) and in his two books, Through Different Eyes and Bang! You’re Dead.

Sight loss ultimately changed the trajectory of Tom’s life and career. At first, he had trouble reconciling the tools that were handed to him – a white cane, magnifiers – with the profound challenges he was newly facing. Once a successful senior investment banker, Tom felt his fast-paced world of finance come to an agonizing halt. Initially, the emotional toll outweighed the practical implications of visual impairment. Tom says he “spent a lot of time trying to point out to people that actually the big thing about sight loss isn’t the loss of sight… but the effect that it has on your emotional well-being… or indeed your level of depression and anxiety, to be a bit more specific. Just that feeling of not being able to cope.”

However, taking the time and effort to redefine his identity and values eventually brought about healing. Tom tackled some hard truths and fundamental questions: what did it mean to be a decent human? A good dad and a good citizen? And how would he make a living with the skills he had, while doing his very best on a day-to-day basis to help others?

Albeit painful, the process of re-evaluating his life’s purpose led Tom to a place of empathy, a deep-seated compassion for others in similar situations. As a result, he came to focus on helping others develop the confidence and resilience necessary to use the tools that would help them live as independently as possible.

Changing course

With a renewed sense of purpose, Tom entered the nonprofit sector, where he served as CEO of the Royal Society for Blind Children (RSBC) following tenures at the Guide Dogs for the Blind Association and the European Guide Dogs Federation.

During this time, Tom led one of the world’s largest studies on blindness in the UK. The study found that “if you wanted blind people to function well, then they have to feel well about themselves,” says Tom. Public services for the blind were somewhat meaningless unless people were genuinely willing to use them. The simple fact that those services exist and that they are free is not enough.

This takeaway represented a shift in perspective on the needs of blind individuals. Practical needs are important, but emotional well-being and mental health must be prioritized. Tom’s focus was on helping people develop the skills, confidence, and resilience needed to confront the practical challenges they faced daily. Only then would they be able to take full advantage of the services and technologies intended to enhance their independence and quality of life.

The inspiration for Waymap

As the chief executive for the RSBC, Tom regularly spoke with groups of visually impaired young people, posing the question, “What are three things we can do to make the world better for you?” In one instance, a young woman shared a wish to use the London Underground metro system without a sighted guide. Relying on a sighted guide to navigate the trains while out on a date with her boyfriend was simply “not cool,” in her opinion.

Tom was in the habit of problem-solving and bringing together highly skilled teams of likeminded people who could turn his ideas into reality. Navigating the Underground independently would require highly accurate assistive technology that would boost a traveler’s confidence. Knowing this, Tom and his colleagues jumped into action.

The first step? They listened. They received a million dollar grant from Google to determine what people with disabilities needed in a navigational app. The Waymap team polled thousands of blind and disabled individuals on their needs and preferences.

The results of their research were encompassed by the first international and American standards for digital navigation for the visually impaired. These standards define what blind people or people with intellectual or developmental disabilities want in terms of a navigational app. For Waymap, they are must-have features.

While designed for people with disabilities, Waymap is intended to be a tool for everyone. As Tom describes, “Although we built it with blind and disabled people at its core, we actually built the app for everyone… When you apply the principles of universal design to an idea such as that, then you have to look at the needs of all clients, be they disabled or able-bodied. Everybody has a unique need for using a navigation app.”

Rolling out in the real world

Waymap was first launched in Washington DC on a rainy spring day in May 2022. After successful trials in three subway stations, Waymap is currently rolling out across the entire WMATA network. Their goal is to be up and running across all 100 stations and 11,000 bus stops in the DC metro area by the spring. With Waymap in place, DC will become one of the most accessible transportation systems in the world, and a replicable model for other cities globally.

Tom says one might think of Waymap as “the search engine of the real world.” It lets users explore their surroundings, much like they would tap into a search engine to explore the digital world. Deploying Waymap gives people real-world feedback to help them circumvent any barriers they may encounter.

Future goals

In Tom’s opinion, technology like Waymap’s will be the driving force behind the services available in smart cities. “The thing that we need to understand,” says Tom, “is that smart cites are now a reality and they’re going to become a bigger reality over time, and technology is going to drive the services in smart cities.” Tom views Waymap as a valuable data source for the locales where it is implemented. Data transparency is key. Waymap is positioned to share its data with cities, showing them how people are using the city and what challenges they face getting around. City leaders can make the most of such quantitative data to help inform their decisions. In Tom’s opinion, it’s one thing to campaign for change, it’s another to provide the hard data that identifies exactly what changes are necessary.

Further, artificial intelligence can be used to find solutions to these navigational challenges. However, Tom warns that AI for smart cities is mostly geared toward the needs of an “average” person, which he believes does not exist. He says we need to be clear that “artificial intelligence as it’s currently being developed for smart cities is a bit like looking at what the ‘average man’ would do… and what we’ve got to do is to say actually, there isn’t an average man, there isn’t an average woman. There are millions of individuals, all of whom have to some degree varying requirements, but huge overlapping requirements. And we need to be able to deal with the huge overlapping requirements and to be able to knock off and deliver on those areas of specialty in a way that is far more efficient than what we’re doing today.” Smart cities must be able to handle the overlap while delivering on specific needs, deftly and efficiently.

In Tom’s opinion, now is the time to tackle this challenge, to focus on improving the algorithms beyond the overly broad, “average man” way of thinking. If successful, smart cities will be able to use location technologies like Waymap’s to deliver services seamlessly and with pinpoint accuracy. For example, a blind individual will be able to order a driverless car, and it will pull up within one meter. That individual will be able to take the car to a restaurant or a work meeting and locate his or her seat without much human intervention. In this manner, more finely tuned algorithms will lead to greater independence and better quality of life for people with disabilities.

The power of acceptance

Nowadays, Tom travels extensively and uses his white cane everywhere he goes. He is a family man at heart, enjoying many an excursion with his wife and kids. He says acceptance was key to finding his new position in life. At first, fear of sight loss sent him spiraling into denial. But in time, he learned the art and practice of acceptance.

Tom describes acceptance as feeling the pain of being in a situation beyond your control, like losing your vision, and coming to terms with your new reality. Once he found acceptance, his confidence grew, he was able to take advantage of the supports around him, and he could move forward in a positive way. Tom puts it best in his own words:

“Once you have accepted the thing, in other words, it is what it is — it’s no longer a ‘but’ thing, it’s an ‘and’ thing. And I am going to do something about it. I am not going to be defeated by this. I am going to live my life to the best of my ability, and all that’s wrong with me is I can’t see properly. And I’m going to use everything I can to augment that, so that I can live the life, the best life that I want to live. And each of us have a best life that we want to live, and just by the process of acceptance we don’t let a sight condition get in the way of that.”

— Tom Pey, CEO, Waymap

Overall, Waymap is not just a helpful tool for finding your way around. Led by a founder who is dedicated to serving the real needs of real people, Waymap aspires to help individuals find the freedom, confidence, and autonomy that are associated with independent travel.

If you want Waymap in your city, you can contact your local representatives to advocate for the app to be made available in your area. You can also reach out to Waymap via their website. We hope many travelers will be able to take advantage of this technology and discover a new way of exploring the world independently.

Last updated Jan. 18, 2023.

Images and video courtesy of Waymap.

Author Information

By Bethany Wyshak. Reviewed by Stuart Flom.

Sources

Gore, N. (2022, May 27). Waymap Announces Partnership With WMATA and the District of Columbia. Waymap. https://waymapnav.com/waymap-partnership-wmata-district-of-columbia/

Visram, T. (2022, July 12). This app gives people who are blind step-by-step audio directions to easily navigate public transit. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/90768125/this-app-gives-people-who-are-blind-step-by-step-audio-directions-to-easily-navigate-public-transit

Copyright © 2023 AdaptiVision, Inc.

Wow, I just read your blog post about Waymap and I have to say, I am truly impressed. The amount of thought and effort that went into developing this technology is evident and it’s clear that it can make a huge difference in the lives of those who are blind or visually impaired. The precision and accuracy of the turn-by-turn navigation is amazing and the fact that it doesn’t require wifi or cell signal is a game-changer. I also love the feature that allows users to receive real-time updates and alternative routes in case of obstacles or outages. This gives users a sense of control and independence that they may not have had before. Overall, I think Waymap is a powerful tool that can help to break down barriers and improve the lives of those who are blind or visually impaired. Keep up the great work!

Agreed! Thanks so much for your feedback and for reading the article!