Eye Conditions

Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a disease that blurs the sharp, central vision you need for “straight-ahead” activities such as reading, sewing, and driving. AMD affects the macula, the part of the eye that allows you to see fine detail. AMD causes no pain.

More Information

What you should know about age-related macular degeneration

Perhaps you have just learned that you or a loved one has age-related macular degeneration, also known as AMD. If you are like many people, you probably do not know a lot about the condition or understand what is going on inside your eyes.

This PAGE will give you a general overview of AMD. You will learn about the following:

- Risk factors and symptoms of AMD

- Treatment options

- Low vision services that help people make the most of their remaining eyesight

- Support groups and others who can help

The aim is to answer your questions and to help relieve some of the anxiety you may be feeling.

What is AMD?

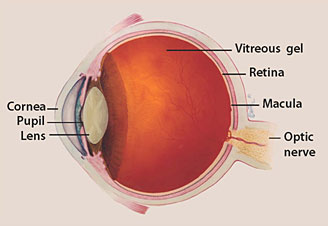

AMD is a common eye condition and a leading cause of vision loss among people age 50 and older. It causes damage to the macula, a small spot near the center of the retina and the part of the eye needed for sharp, central vision, which lets us see objects that are straight ahead.

In some people, AMD advances so slowly that vision loss does not occur for a long time. In others, the disease progresses faster and may lead to a loss of vision in one or both eyes. As AMD progresses, a blurred area near the center of vision is a common symptom. Over time, the blurred area may grow larger or you may develop blank spots in your central vision. Objects also may not appear to be as bright as they used to be.

AMD by itself does not lead to complete blindness, with no ability to see. However, the loss of central vision in AMD can interfere with simple everyday activities, such as the ability to see faces, drive, read, write, or do close work, such as cooking or fixing things around the house.

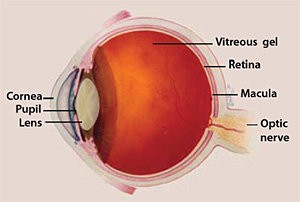

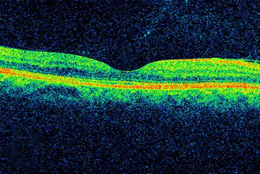

The Macula

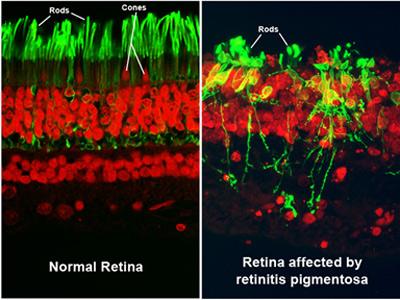

The macula is made up of millions of light-sensing cells that provide sharp, central vision. It is the most sensitive part of the retina, which is located at the back of the eye. The retina turns light into electrical signals and then sends these electrical signals through the optic nerve to the brain, where they are translated into the images we see. When the macula is damaged, the center of your field of view may appear blurry, distorted, or dark.

Who is at risk?

Age is a major risk factor for AMD. The disease is most likely to occur after age 60, but it can occur earlier. Other risk factors for AMD include:

- Smoking. Research shows that smoking doubles the risk of AMD.

- Race. AMD is more common among Caucasians than among African-Americans or Hispanics/Latinos.

- Family history and Genetics. People with a family history of AMD are at higher risk. At last count, researchers had identified nearly 20 genes that can affect the risk of developing AMD. Many more genetic risk factors are suspected.

You may see offers for genetic testing for AMD. Because AMD is influenced by so many genes plus environmental factors such as smoking and nutrition, there are currently no genetic tests that can diagnose AMD, or predict with certainty who will develop it.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology(link is external) currently recommends against routine genetic testing for AMD, and insurance generally does not cover such testing.

Does lifestyle make a difference?

Researchers have found links between AMD and some lifestyle choices, such as smoking. You might be able to reduce your risk of AMD or slow its progression by making these healthy choices:

- Avoid smoking

- Exercise regularly

- Maintain normal blood pressure and cholesterol levels

- Eat a healthy diet rich in green, leafy vegetables and fish

How is AMD detected?

The early and intermediate stages of AMD usually start without symptoms. Only a comprehensive dilated eye exam can detect AMD. The eye exam may include the following:

- Visual acuity test. This eye chart measures how well you see at distances.

- Dilated eye exam. Your eye care professional places drops in your eyes to widen or dilate the pupils. This provides a better view of the back of your eye. Using a special magnifying lens, he or she then looks at your retina and optic nerve for signs of AMD and other eye problems.

- Amsler grid. Your eye care professional also may ask you to look at an Amsler grid. Changes in your central vision may cause the lines in the grid to disappear or appear wavy, a sign of AMD.

- Fluorescein angiogram. In this test, which is performed by an ophthalmologist, a fluorescent dye is injected into your arm. Pictures are taken as the dye passes through the blood vessels in your eye. This makes it possible to see leaking blood vessels, which occur in a severe, rapidly progressive type of AMD (see below). In rare cases, complications to the injection can arise, from nausea to more severe allergic reactions.

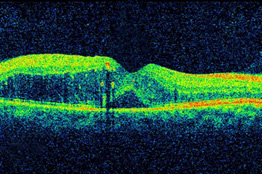

- Optical coherence tomography. You have probably heard of ultrasound, which uses sound waves to capture images of living tissues. OCT is similar except that it uses light waves, and can achieve very high-resolution images of any tissues that can be penetrated by light—such as the eyes. After your eyes are dilated, you’ll be asked to place your head on a chin rest and hold still for several seconds while the images are obtained. The light beam is painless.

During the exam, your eye care professional will look for drusen, which are yellow deposits beneath the retina. Most people develop some very small drusen as a normal part of aging. The presence of medium-to-large drusen may indicate that you have AMD.

Another sign of AMD is the appearance of pigmentary changes under the retina. In addition to the pigmented cells in the iris (the colored part of the eye), there are pigmented cells beneath the retina. As these cells break down and release their pigment, your eye care professional may see dark clumps of released pigment and later, areas that are less pigmented. These changes will not affect your eye color.

Questions to ask your eye care Professional

Below are a few questions you may want to ask your eye care professional to help you understand your diagnosis and treatment. If you do not understand your eye care professional’s responses, ask questions until you do understand.

- What is my diagnosis and how do you spell the name of the condition?

- Can my AMD be treated?

- How will this condition affect my vision now and in the future?

- What symptoms should I watch for and how should I notify you if they occur?

- Should I make lifestyle changes?

What are the stages of AMD?

There are three stages of AMD defined in part by the size and number of drusen under the retina. It is possible to have AMD in one eye only, or to have one eye with a later stage of AMD than the other.

- Early AMD. Early AMD is diagnosed by the presence of medium-sized drusen, which are about the width of an average human hair. People with early AMD typically do not have vision loss.

- Intermediate AMD. People with intermediate AMD typically have large drusen, pigment changes in the retina, or both. Again, these changes can only be detected during an eye exam. Intermediate AMD may cause some vision loss, but most people will not experience any symptoms.

- Late AMD. In addition to drusen, people with late AMD have vision loss from damage to the macula. There are two types of late AMD:

- In geographic atrophy (also called dry AMD), there is a gradual breakdown of the light-sensitive cells in the macula that convey visual information to the brain, and of the supporting tissue beneath the macula. These changes cause vision loss.

- In neovascular AMD (also called wet AMD), abnormal blood vessels grow underneath the retina. (“Neovascular” literally means “new vessels.”) These vessels can leak fluid and blood, which may lead to swelling and damage of the macula. The damage may be rapid and severe, unlike the more gradual course of geographic atrophy. It is possible to have both geographic atrophy and neovascular AMD in the same eye, and either condition can appear first.

AMD has few symptoms in the early stages, so it is important to have your eyes examined regularly. If you are at risk for AMD because of age, family history, lifestyle, or some combination of these factors, you should not wait to experience changes in vision before getting checked for AMD.

Not everyone with early AMD will develop late AMD. For people who have early AMD in one eye and no signs of AMD in the other eye, about five percent will develop advanced AMD after 10 years. For people who have early AMD in both eyes, about 14 percent will develop late AMD in at least one eye after 10 years. With prompt detection of AMD, there are steps you can take to further reduce your risk of vision loss from late AMD.

If you have late AMD in one eye only, you may not notice any changes in your overall vision. With the other eye seeing clearly, you may still be able to drive, read, and see fine details. However, having late AMD in one eye means you are at increased risk for late AMD in your other eye. If you notice distortion or blurred vision, even if it doesn’t have much effect on your daily life, consult an eye care professional.

How is AMD treated?

Early AMD

Currently, no treatment exists for early AMD, which in many people shows no symptoms or loss of vision. Your eye care professional may recommend that you get a comprehensive dilated eye exam at least once a year. The exam will help determine if your condition is advancing.

As for prevention, AMD occurs less often in people who exercise, avoid smoking, and eat nutritious foods including green leafy vegetables and fish. If you already have AMD, adopting some of these habits may help you keep your vision longer.

Intermediate and late AMD

Researchers at the National Eye Institute tested whether taking nutritional supplements could protect against AMD in the Age-Related Eye Disease Studies (AREDS and AREDS2). They found that daily intake of certain high-dose vitamins and minerals can slow progression of the disease in people who have intermediate AMD, and those who have late AMD in one eye.

The first AREDS trial showed that a combination of vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, zinc, and copper can reduce the risk of late AMD by 25 percent. The AREDS2 trial tested whether this formulation could be improved by adding lutein, zeaxanthin or omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 fatty acids are nutrients enriched in fish oils. Lutein, zeaxanthin and beta-carotene all belong to the same family of vitamins, and are abundant in green leafy vegetables.

The AREDS2 trial found that adding lutein and zeaxanthin or omega-three fatty acids to the original AREDS formulation (with beta-carotene) had no overall effect on the risk of late AMD. However, the trial also found that replacing beta-carotene with a 5-to-1 mixture of lutein and zeaxanthin may help further reduce the risk of late AMD. Moreover, while beta-carotene has been linked to an increased risk of lung cancer in current and former smokers, lutein and zeaxanthin appear to be safe regardless of smoking status.

Here are the clinically effective doses tested in AREDS and AREDS2:

- 500 milligrams (mg) of vitamin C

- 400 international units of vitamin E

- 80 mg zinc as zinc oxide (25 mg in AREDS2)

- 2 mg copper as cupric oxide

- 15 mg beta-carotene, OR 10 mg lutein and 2 mg zeaxanthin

A number of manufacturers offer nutritional supplements that were formulated based on these studies. The label may refer to “AREDS” or “AREDS2.”

If you have intermediate or late AMD, you might benefit from taking such supplements. But first, be sure to review and compare the labels. Many of the supplements have different ingredients, or different doses, from those tested in the AREDS trials. Also, consult your doctor or eye care professional about which supplement, if any, is right for you. For example, if you smoke regularly, or used to, your doctor may recommend that you avoid supplements containing beta-carotene.

Even if you take a daily multivitamin, you should consider taking an AREDS supplement if you are at risk for late AMD. The formulations tested in the AREDS trials contain much higher doses of vitamins and minerals than what is found in multivitamins. Tell your doctor or eye care professional about any multivitamins you are taking when you are discussing possible AREDS formulations.

You may see claims that your specific genetic makeup (genotype) can influence how you will respond to AREDS supplements. Some recent studies have claimed that, depending on genotype, some patients will benefit from AREDS supplements and others could be harmed. These claims are based on a portion of data from the AREDS research. NEI investigators have done comprehensive analyses of the complete AREDS data. Their findings to date indicate that AREDS supplements are beneficial for patients of all tested genotypes. Based on the overall data, the American Academy of Ophthalmology(link is external) does not support the use of genetic testing to guide treatment for AMD.

Finally, remember that the AREDS formulation is not a cure. It does not help people with early AMD, and will not restore vision already lost from AMD. But it may delay the onset of late AMD. It also may help slow vision loss in people who already have late AMD.

Advanced neovascular AMD

Neovascular AMD typically results in severe vision loss. However, eye care professionals can try different therapies to stop further vision loss. You should remember that the therapies described below are not a cure. The condition may progress even with treatment.

- Injections. One option to slow the progression of neovascular AMD is to inject drugs into the eye. With neovascular AMD, abnormally high levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are secreted in your eyes. VEGF is a protein that promotes the growth of new abnormal blood vessels. Anti-VEGF injection therapy blocks this growth. If you get this treatment, you may need multiple monthly injections. Before each injection, your eye will be numbed and cleaned with antiseptics. To further reduce the risk of infection, you may be prescribed antibiotic drops. A few different anti-VEGF drugs are available. They vary in cost and in how often they need to be injected, so you may wish to discuss these issues with your eye care professional.

- Photodynamic therapy. This technique involves laser treatment of select areas of the retina. First, a drug called verteporfin will be injected into a vein in your arm. The drug travels through the blood vessels in your body, and is absorbed by new, growing blood vessels. Your eye care professional then shines a laser beam into your eye to activate the drug in the new abnormal blood vessels, while sparing normal ones. Once activated, the drug closes off the new blood vessels, slows their growth, and slows the rate of vision loss. This procedure is less common than anti-VEGF injections, and is often used in combination with them for specific types of neovascular AMD.

- Laser surgery. Eye care professionals treat certain cases of neovascular AMD with laser surgery, though this is less common than other treatments. It involves aiming an intense “hot” laser at the abnormal blood vessels in your eyes to destroy them. This laser is not the same one used in photodynamic therapy which may be referred to as a “cold” laser. This treatment is more likely to be used when blood vessel growth is limited to a compact area in your eye, away from the center of the macula, that can be easily targeted with the laser. Even so, laser treatment also may destroy some surrounding healthy tissue. This often results in a small blind spot where the laser has scarred the retina. In some cases, vision immediately after the surgery may be worse than it was before. But the surgery may also help prevent more severe vision loss from occurring years later.

Questions to ask your eye care professional about treatment

- What is the treatment for advanced neovascular AMD?

- When will treatment start and how long will it last?

- What are the benefits of this treatment and how successful is it?

- What are the risks and side effects associated with this treatment and how has this information been gathered?

- Should I avoid certain foods, drugs, or activities while I am undergoing treatment?

- Are other treatments available?

- When should I follow up after treatment?

Loss of Vision

Coping with AMD and vision loss can be a traumatic experience. This is especially true if you have just begun to lose your vision or have low vision. Having low vision means that even with regular glasses, contact lenses, medicine, or surgery, you find everyday tasks difficult to do. Reading the mail, shopping, cooking, and writing can all seem challenging.

However, help is available. You may not be able to restore your vision, but low vision services can help you make the most of what is remaining. You can continue enjoying friends, family, hobbies, and other interests just as you always have. The key is to not delay use of these services.

What is vision rehabilitation?

To cope with vision loss, you must first have an excellent support team. This team should include you, your primary eye care professional, and an optometrist or ophthalmologist specializing in low vision. Occupational therapists, orientation and mobility specialists, certified low vision therapists, counselors, and social workers are also available to help. Together, the low vision team can help you make the most of your remaining vision and maintain your independence.

Second, talk with your eye care professional about your vision problems. Ask about vision rehabilitation, even if your eye care professional says that “nothing more can be done for your vision.” Vision rehabilitation programs offer a wide range of services, including training for magnifying and adaptive devices, ways to complete daily living skills safely and independently, guidance on modifying your home, and information on where to locate resources and support to help you cope with your vision loss.

Medicare may cover part or all of a patient’s occupational therapy, but the therapy must be ordered by a doctor and provided by a Medicare—approved healthcare provider. To see if you are eligible for Medicare—funded occupational therapy, call 1—800—MEDICARE or 1—800—633—4227.

Where to go for services

Low vision services can take place in different locations, including:

- Ophthalmology or optometry offices that specialize in low vision

- Hospital clinics

- State, nonprofit, or for-profit vision rehabilitation organizations

- Independent-living centers

What are some low vision devices?

Because low vision varies from person to person, specialists have different tools to help patients deal with vision loss. They include:

- Reading glasses with high-powered lenses

- Handheld magnifiers

- Video magnifiers

- Computers with large-print and speech-output systems

- Large-print reading materials

- Talking watches, clocks, and calculators

- Computer aids and other technologies, such as a closed-circuit television, which uses a camera and television to enlarge printed text

For some patients with end-stage AMD, an Implantable Miniature Telescope (IMT) may be an option. This FDA-approved device can help restore some lost vision by refocusing images onto a healthier part of the retina. After the surgery to implant the IMT, patients participate in an extensive vision rehabilitation program.

Keep in mind that low vision aids without proper diagnosis, evaluation, and training may not work for you. It is important that you work closely with your low vision team to get the best device or combination of aids to help improve your ability to see.

Questions to ask your eye care professional about low vision

- How can I continue my normal, routine activities?

- Are there resources to help me?

- Will any special devices help me with reading, cooking, or fixing things around the house?

- What training is available to me?

- Where can I find individual or group support to cope with my vision loss?

Charles Bonnet syndrome (Visual Hallucinations)

People with impaired vision sometimes see things that are not there, called visual hallucinations. They may see simple patterns of colors or shapes, or detailed pictures of people, animals, buildings, or landscapes. Sometimes these images fit logically into a visual scene, but they often do not.

This condition can be alarming, but don’t worry—it is not a sign of mental illness. It is called Charles Bonnet syndrome, and it is similar to what happens to some people who have lost an arm or leg. Even though the limb is gone, these people still feel their toes or fingers or experience itching. Similarly, when the brain loses input from the eyes, it may fill the void by generating visual images on its own.

Charles Bonnet syndrome is a common side effect of vision loss in people with AMD. However, it often goes away a year to 18 months after it begins. In the meantime, there are things you can do to reduce hallucinations. Many people find the hallucinations occur more frequently in evening or dim light. Turning on a light or television may help. It may also help to blink, close your eyes, or focus on a real object for a few moments.

Coping with AMD

AMD and vision loss can profoundly affect your life. This is especially true if you lose your vision rapidly.

Even if you experience gradual vision loss, you may not be able to live your life the way you used to. You may need to cut back on working, volunteering, and recreational activities. Your relationships may change, and you may need more help from family and friends than you are used to. These changes can lead to feelings of loss, lowered self-esteem, isolation, and depression.

In addition to getting medical treatment for AMD, there are things you can do to cope:

- Learn more about your vision loss.

- Visit a specialist in low vision and get devices and learning skills to help you with the tasks of everyday living.

- Try to stay positive. People who remain hopeful say they are better able to cope with AMD and vision loss.

- Stay engaged with family and friends.

- Seek a professional counselor or support group. Your doctor or eye care professional may be able to refer you to one.

Information for family members

Shock, disbelief, depression, and anger are common reactions among people who are diagnosed with AMD. These feelings can subside after a few days or weeks, or they may last longer. This can be upsetting to family members and caregivers who are trying to be as caring and supportive as possible.

Following are some ideas family members might consider:

- Obtain as much information as possible about AMD and how it affects sight. Share the information with the person who has AMD.

- Find support groups and other resources within the community.

- Encourage family and friends to visit and support the person with AMD.

- Allow for grieving. This is a natural process.

- Lend support by “being there.”

What research is being done?

NEI conducts and supports research in labs and clinical centers across the country to better prevent, detect, and treat AMD.

NEI-funded research over the past decade has revealed new insight into the genetics of AMD. By screening the DNA of thousands of people with and without AMD, scientists have identified differences in genes that affect AMD risk. Armed with this knowledge, researchers are identifying key biochemical pathways involved in the disease and are exploring therapies that could interrupt these pathways. It might also be possible to develop drug therapies for AMD that are targeted specifically to a person’s unique genetic risk factors.

Scientists are also exploring ways to regenerate tissues destroyed by AMD. One approach is to make stem cells from a patient’s own skin or blood. In a lab, these stem cells can be specially treated to form sheets of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)—the pigmented layer of tissue that supports the light-sensitive cells of the retina. The goal is to generate layers of RPE that can be implanted into the patient’s eye to preserve vision.

The NEI Audacious Goals Initiative (AGI) is taking on one of the biggest challenges in medicine: the regeneration of nerve cells in the retina and brain. In humans, once brain and retinal neurons are gone—due to injury or diseases like AMD—they are typically gone for good. However, lessons from nature suggest that it may possible to overcome this limitation. For example, in some fish and amphibians, if the retina is damaged, it can grow back. Through targeted research, the NEI AGI aims to unlock these secrets and utilize them in humans—to develop new therapies to regenerate neurons and neural connections in the eye and visual system.

Where can I get more information?

The National Eye Institute (NEI) is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and is the Federal government’s lead agency for vision research that leads to sight-saving treatments and plays a key role in reducing visual impairment and blindness.

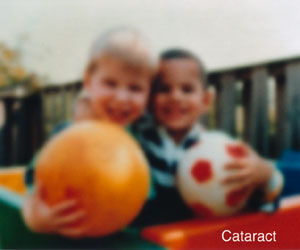

Cataract

A cataract is a clouding of the lens in the eye that affects vision. Most cataracts are related to aging. Cataracts are very common in older people. By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a cataract or have had cataract surgery.

More Information

About Cataracts

What is a cataract?

A cataract is a clouding of the lens in the eye that affects vision. Most cataracts are related to aging. Cataracts are very common in older people. By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a cataract or have had cataract surgery.

A cataract can occur in either or both eyes. It cannot spread from one eye to the other.

What is the lens?

The lens is a clear part of the eye that helps to focus light, or an image, on the retina. The retina is the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye.

In a normal eye, light passes through the transparent lens to the retina. Once it reaches the retina, light is changed into nerve signals that are sent to the brain.

The lens must be clear for the retina to receive a sharp image. If the lens is cloudy from a cataract, the image you see will be blurred.

Normal vision

The same scene as viewed by a person with cataract

What causes cataracts?

The lens lies behind the iris and the pupil. It works much like a camera lens. It focuses light onto the retina at the back of the eye, where an image is recorded. The lens also adjusts the eye’s focus, letting us see things clearly both up close and far away. The lens is made of mostly water and protein. The protein is arranged in a precise way that keeps the lens clear and lets light pass through it.

But as we age, some of the protein may clump together and start to cloud a small area of the lens. This is a cataract. Over time, the cataract may grow larger and cloud more of the lens, making it harder to see.

Researchers suspect that there are several causes of cataract, such as smoking and diabetes. Or, it may be that the protein in the lens just changes from the wear and tear it takes over the years.

How do cataracts affect vision?

Age-related cataracts can affect your vision in two ways:

- Clumps of protein reduce the sharpness of the image reaching the retina.The lens consists mostly of water and protein. When the protein clumps up, it clouds the lens and reduces the light that reaches the retina. The clouding may become severe enough to cause blurred vision. Most age-related cataracts develop from protein clumpings.When a cataract is small, the cloudiness affects only a small part of the lens. You may not notice any changes in your vision. Cataracts tend to “grow” slowly, so vision gets worse gradually. Over time, the cloudy area in the lens may get larger, and the cataract may increase in size. Seeing may become more difficult. Your vision may get duller or blurrier.

- The clear lens slowly changes to a yellowish/brownish color, adding a brownish tint to vision.As the clear lens slowly colors with age, your vision gradually may acquire a brownish shade. At first, the amount of tinting may be small and may not cause a vision problem. Over time, increased tinting may make it more difficult to read and perform other routine activities. This gradual change in the amount of tinting does not affect the sharpness of the image transmitted to the retina.If you have advanced lens discoloration, you may not be able to identify blues and purples. You may be wearing what you believe to be a pair of black socks, only to find out from friends that you are wearing purple socks.

When are you most likely to have a cataract?

The term “age-related” is a little misleading. You don’t have to be a senior citizen to get this type of cataract. In fact, people can have an age-related cataract in their 40s and 50s. But during middle age, most cataracts are small and do not affect vision. It is after age 60 that most cataracts cause problems with a person’s vision.

Who is at risk for cataract?

The risk of cataract increases as you get older. Other risk factors for cataract include:

- Certain diseases (for example, diabetes).

- Personal behavior (smoking, alcohol use.

- The environment (prolonged exposure to ultraviolet sunlight).

What are the symptoms of a cataract?

The most common symptoms of a cataract are:

- Cloudy or blurry vision.

- Colors seem faded.

- Glare. Headlights, lamps, or sunlight may appear too bright. A halo may appear around lights.

- Poor night vision.

- Double vision or multiple images in one eye. (This symptom may clear as the cataract gets larger.)

- Frequent prescription changes in your eyeglasses or contact lenses.

These symptoms also can be a sign of other eye problems. If you have any of these symptoms, check with your eye care professional.

Are there different types of cataract?

Yes. Although most cataracts are related to aging, there are other types of cataract:

-

- Secondary cataract. Cataracts can form after surgery for other eye problems, such as glaucoma. Cataracts also can develop in people who have other health problems, such as diabetes. Cataracts are sometimes linked to steroid use.

- Traumatic cataract. Cataracts can develop after an eye injury, sometimes years later.

- Congenital cataract. Some babies are born with cataracts or develop them in childhood, often in both eyes. These cataracts may be so small that they do not affect vision. If they do, the lenses may need to be removed.

- Radiation cataract. Cataracts can develop after exposure to some types of radiation.

How is a cataract detected?

Cataract is detected through a comprehensive eye exam that includes:

-

-

- Visual acuity test. This eye chart test measures how well you see at various distances.

- Dilated eye exam. Drops are placed in your eyes to widen, or dilate, the pupils. Your eye care professional uses a special magnifying lens to examine your retina and optic nerve for signs of damage and other eye problems. After the exam, your close-up vision may remain blurred for several hours.

- Tonometry. An instrument measures the pressure inside the eye. Numbing drops may be applied to your eye for this test.

-

Your eye care professional also may do other tests to learn more about the structure and health of your eye.

Treatment

How is a cataract treated?

The symptoms of early cataract may be improved with new eyeglasses, brighter lighting, anti-glare sunglasses, or magnifying lenses. If these measures do not help, surgery is the only effective treatment. Surgery involves removing the cloudy lens and replacing it with an artificial lens.

A cataract needs to be removed only when vision loss interferes with your everyday activities, such as driving, reading, or watching TV. You and your eye care professional can make this decision together. Once you understand the benefits and risks of surgery, you can make an informed decision about whether cataract surgery is right for you. In most cases, delaying cataract surgery will not cause long-term damage to your eye or make the surgery more difficult. You do not have to rush into surgery.

Sometimes a cataract should be removed even if it does not cause problems with your vision. For example, a cataract should be removed if it prevents examination or treatment of another eye problem, such as age-related macular degeneration or diabetic retinopathy.

If you choose surgery, your eye care professional may refer you to a specialist to remove the cataract.

If you have cataracts in both eyes that require surgery, the surgery will be performed on each eye at separate times, usually four weeks apart.

Is cataract surgery effective?

Cataract removal is one of the most common operations performed in the United States. It also is one of the safest and most effective types of surgery. In about 90 percent of cases, people who have cataract surgery have better vision afterward.

What are the risks of cataract surgery?

As with any surgery, cataract surgery poses risks, such as infection and bleeding. Before cataract surgery, your doctor may ask you to temporarily stop taking certain medications that increase the risk of bleeding during surgery. After surgery, you must keep your eye clean, wash your hands before touching your eye, and use the prescribed medications to help minimize the risk of infection. Serious infection can result in loss of vision.

Cataract surgery slightly increases your risk of retinal detachment. Other eye disorders, such as high myopia (nearsightedness), can further increase your risk of retinal detachment after cataract surgery. One sign of a retinal detachment is a sudden increase in flashes or floaters. Floaters are little “cobwebs” or specks that seem to float about in your field of vision. If you notice a sudden increase in floaters or flashes, see an eye care professional immediately. A retinal detachment is a medical emergency. If necessary, go to an emergency service or hospital. Your eye must be examined by an eye surgeon as soon as possible. A retinal detachment causes no pain. Early treatment for retinal detachment often can prevent permanent loss of vision. The sooner you get treatment, the more likely you will regain good vision. Even if you are treated promptly, some vision may be lost.

Talk to your eye care professional about these risks. Make sure cataract surgery is right for you.

What if I have other eye conditions and need cataract surgery?

Many people who need cataract surgery also have other eye conditions, such as age-related macular degeneration or glaucoma. If you have other eye conditions in addition to cataract, talk with your doctor. Learn about the risks, benefits, alternatives, and expected results of cataract surgery.

What happens before surgery?

A week or two before surgery, your doctor will do some tests. These tests may include measuring the curve of the cornea and the size and shape of your eye. This information helps your doctor choose the right type of intraocular lens (IOL).

You may be asked not to eat or drink anything 12 hours before your surgery.

What happens during surgery?

At the hospital or eye clinic, drops will be put into your eye to dilate the pupil. The area around your eye will be washed and cleansed.

The operation usually lasts less than one hour and is almost painless. Many people choose to stay awake during surgery. Others may need to be put to sleep for a short time. If you are awake, you will have an anesthetic to numb the nerves in and around your eye.

After the operation, a patch may be placed over your eye. You will rest for a while. Your medical team will watch for any problems, such as bleeding. Most people who have cataract surgery can go home the same day. You will need someone to drive you home.

What happens after surgery?

Itching and mild discomfort are normal after cataract surgery. Some fluid discharge is also common. Your eye may be sensitive to light and touch. If you have discomfort, your doctor can suggest treatment. After one or two days, moderate discomfort should disappear.

For a few weeks after surgery, your doctor may ask you to use eyedrops to help healing and decrease the risk of infection. Ask your doctor about how to use your eyedrops, how often to use them, and what effects they can have. You will need to wear an eye shield or eyeglasses to help protect your eye. Avoid rubbing or pressing on your eye.

When you are home, try not to bend from the waist to pick up objects on the floor. Do not lift any heavy objects. You can walk, climb stairs, and do light household chores.

In most cases, healing will be complete within eight weeks. Your doctor will schedule exams to check on your progress.

Can problems develop after surgery?

Problems after surgery are rare, but they can occur. These problems can include infection, bleeding, inflammation (pain, redness, swelling), loss of vision, double vision, and high or low eye pressure. With prompt medical attention, these problems can usually be treated successfully.

Sometimes the eye tissue that encloses the IOL becomes cloudy and may blur your vision. This condition is called an after-cataract. An after-cataract can develop months or years after cataract surgery.

An after-cataract is treated with a laser. Your doctor uses a laser to make a tiny hole in the eye tissue behind the lens to let light pass through. This outpatient procedure is called a YAG laser capsulotomy. It is painless and rarely results in increased eye pressure or other eye problems. As a precaution, your doctor may give you eyedrops to lower your eye pressure before or after the procedure.

When will my vision be normal again?

You can return quickly to many everyday activities, but your vision may be blurry. The healing eye needs time to adjust so that it can focus properly with the other eye, especially if the other eye has a cataract. Ask your doctor when you can resume driving.

If you received an IOL, you may notice that colors are very bright. The IOL is clear, unlike your natural lens that may have had a yellowish/brownish tint. Within a few months after receiving an IOL, you will become used to improved color vision. Also, when your eye heals, you may need new glasses or contact lenses.

What can I do if I already have lost some vision from cataract?

If you have lost some vision, speak with your surgeon about options that may help you make the most of your remaining vision.

What can I do to protect my vision?

Wearing sunglasses and a hat with a brim to block ultraviolet sunlight may help to delay cataract. If you smoke, stop. Researchers also believe good nutrition can help reduce the risk of age-related cataract. They recommend eating green leafy vegetables, fruit, and other foods with antioxidants.

If you are age 60 or older, you should have a comprehensive dilated eye exam at least once every two years. In addition to cataract, your eye care professional can check for signs of age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, and other vision disorders. Early treatment for many eye diseases may save your sight.

What research is being done?

The National Eye Institute is conducting and supporting a number of studies focusing on factors associated with the development of age-related cataract. These studies include:

- The effect of sunlight exposure, which may be associated with an increased risk of cataract.

- Vitamin supplements, which have shown varying results in delaying the progression of cataract.

- Genetic studies, which show promise for better understanding cataract development.

Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic eye disease refers to a group of eye problems that people with diabetes may face as a complication of diabetes. People with diabetes are at risk for diabetic retinopathy, cataract and glaucoma.

More Information

Facts About Diabetic Eye Disease

Points to Remember

- Diabetic eye disease comprises a group of eye conditions that affect people with diabetes. These conditions include diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema (DME), cataract, and glaucoma.

- All forms of diabetic eye disease have the potential to cause severe vision loss and blindness.

- Diabetic retinopathy involves changes to retinal blood vessels that can cause them to bleed or leak fluid, distorting vision.

- Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of vision loss among people with diabetes and a leading cause of blindness among working-age adults.

- DME is a consequence of diabetic retinopathy that causes swelling in the area of the retina called the macula.

- Controlling diabetes—by taking medications as prescribed, staying physically active, and maintaining a healthy diet—can prevent or delay vision loss.

- Because diabetic retinopathy often goes unnoticed until vision loss occurs, people with diabetes should get a comprehensive dilated eye exam at least once a year.

- Early detection, timely treatment, and appropriate follow-up care of diabetic eye disease can protect against vision loss.

- Diabetic retinopathy can be treated with several therapies, used alone or in combination.

- NEI supports research to develop new therapies for diabetic retinopathy, and to compare the effectiveness of existing therapies for different patient groups.

What is diabetic eye disease?

Diabetic eye disease can affect many parts of the eye, including the retina, macula, lens and the optic nerve.

Diabetic eye disease is a group of eye conditions that can affect people with diabetes.

- Diabetic retinopathy affects blood vessels in the light-sensitive tissue called the retina that lines the back of the eye. It is the most common cause of vision loss among people with diabetes and the leading cause of vision impairment and blindness among working-age adults.

- Diabetic macular edema (DME). A consequence of diabetic retinopathy, DME is swelling in an area of the retina called the macula.

Diabetic eye disease also includes cataract and glaucoma:

- Cataract is a clouding of the eye’s lens. Adults with diabetes are 2-5 times more likely than those without diabetes to develop cataract. Cataract also tends to develop at an earlier age in people with diabetes.

- Glaucoma is a group of diseases that damage the eye’s optic nerve—the bundle of nerve fibers that connects the eye to the brain. Some types of glaucoma are associated with elevated pressure inside the eye. In adults, diabetes nearly doubles the risk of glaucoma.

All forms of diabetic eye disease have the potential to cause severe vision loss and blindness.

Diabetic Retinopathy

What causes diabetic retinopathy?

Chronically high blood sugar from diabetes is associated with damage to the tiny blood vessels in the retina, leading to diabetic retinopathy. The retina detects light and converts it to signals sent through the optic nerve to the brain. Diabetic retinopathy can cause blood vessels in the retina to leak fluid or hemorrhage (bleed), distorting vision. In its most advanced stage, new abnormal blood vessels proliferate (increase in number) on the surface of the retina, which can lead to scarring and cell loss in the retina.

Diabetic retinopathy may progress through four stages:

- Mild nonproliferative retinopathy. Small areas of balloon-like swelling in the retina’s tiny blood vessels, called microaneurysms, occur at this earliest stage of the disease. These microaneurysms may leak fluid into the retina.

- Moderate nonproliferative retinopathy. As the disease progresses, blood vessels that nourish the retina may swell and distort. They may also lose their ability to transport blood. Both conditions cause characteristic changes to the appearance of the retina and may contribute to DME.

- Severe nonproliferative retinopathy. Many more blood vessels are blocked, depriving blood supply to areas of the retina. These areas secrete growth factors that signal the retina to grow new blood vessels.

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). At this advanced stage, growth factors secreted by the retina trigger the proliferation of new blood vessels, which grow along the inside surface of the retina and into the vitreous gel, the fluid that fills the eye. The new blood vessels are fragile, which makes them more likely to leak and bleed. Accompanying scar tissue can contract and cause retinal detachment—the pulling away of the retina from underlying tissue, like wallpaper peeling away from a wall. Retinal detachment can lead to permanent vision loss.

What is diabetic macular edema (DME)?

DME is the build-up of fluid (edema) in a region of the retina called the macula. The macula is important for the sharp, straight-ahead vision that is used for reading, recognizing faces, and driving. DME is the most common cause of vision loss among people with diabetic retinopathy. About half of all people with diabetic retinopathy will develop DME. Although it is more likely to occur as diabetic retinopathy worsens, DME can happen at any stage of the disease.

Who is at risk for diabetic retinopathy?

People with all types of diabetes (type 1, type 2, and gestational) are at risk for diabetic retinopathy. Risk increases the longer a person has diabetes. Between 40 and 45 percent of Americans diagnosed with diabetes have some stage of diabetic retinopathy, although only about half are aware of it. Women who develop or have diabetes during pregnancy may have rapid onset or worsening of diabetic retinopathy.

Symptoms and Detection

What are the symptoms of diabetic retinopathy and DME?

The same scene as viewed by a person normal vision (Top) and with (Center) advanced diabetic retinopathy. The floating spots are hemorrhages that require prompt treatment. DME (Bottom) causes blurred vision.

The early stages of diabetic retinopathy usually have no symptoms. The disease often progresses unnoticed until it affects vision. Bleeding from abnormal retinal blood vessels can cause the appearance of “floating” spots. These spots sometimes clear on their own. But without prompt treatment, bleeding often recurs, increasing the risk of permanent vision loss. If DME occurs, it can cause blurred vision.

How are diabetic retinopathy and DME detected?

Diabetic retinopathy and DME are detected during a comprehensive dilated eye exam that includes:

- Visual acuity testing. This eye chart test measures a person’s ability to see at various distances.

- Tonometry. This test measures pressure inside the eye.

- Pupil dilation. Drops placed on the eye’s surface dilate (widen) the pupil, allowing a physician to examine the retina and optic nerve.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT). This technique is similar to ultrasound but uses light waves instead of sound waves to capture images of tissues inside the body. OCT provides detailed images of tissues that can be penetrated by light, such as the eye.

A comprehensive dilated eye exam allows the doctor to check the retina for:

- Changes to blood vessels

- Leaking blood vessels or warning signs of leaky blood vessels, such as fatty deposits

- Swelling of the macula (DME)

- Changes in the lens

- Damage to nerve tissue

If DME or severe diabetic retinopathy is suspected, a fluorescein angiogram may be used to look for damaged or leaky blood vessels. In this test, a fluorescent dye is injected into the bloodstream, often into an arm vein. Pictures of the retinal blood vessels are taken as the dye reaches the eye.

Prevention and Treatment

How can people with diabetes protect their vision?

Vision lost to diabetic retinopathy is sometimes irreversible. However, early detection and treatment can reduce the risk of blindness by 95 percent. Because diabetic retinopathy often lacks early symptoms, people with diabetes should get a comprehensive dilated eye exam at least once a year. People with diabetic retinopathy may need eye exams more frequently. Women with diabetes who become pregnant should have a comprehensive dilated eye exam as soon as possible. Additional exams during pregnancy may be needed.

Studies such as the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) have shown that controlling diabetes slows the onset and worsening of diabetic retinopathy. DCCT study participants who kept their blood glucose level as close to normal as possible were significantly less likely than those without optimal glucose control to develop diabetic retinopathy, as well as kidney and nerve diseases. Other trials have shown that controlling elevated blood pressure and cholesterol can reduce the risk of vision loss among people with diabetes.

Treatment for diabetic retinopathy is often delayed until it starts to progress to PDR, or when DME occurs. Comprehensive dilated eye exams are needed more frequently as diabetic retinopathy becomes more severe. People with severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy have a high risk of developing PDR and may need a comprehensive dilated eye exam as often as every 2 to 4 months.

How is DME treated?

DME can be treated with several therapies that may be used alone or in combination.

Anti-VEGF Injection Therapy. Anti-VEGF drugs are injected into the vitreous gel to block a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which can stimulate abnormal blood vessels to grow and leak fluid. Blocking VEGF can reverse abnormal blood vessel growth and decrease fluid in the retina. Available anti-VEGF drugs include Avastin (bevacizumab), Lucentis (ranibizumab), and Eylea (aflibercept). Lucentis and Eylea are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating DME. Avastin was approved by the FDA to treat cancer, but is commonly used to treat eye conditions, including DME.

The NEI-sponsored Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network compared Avastin, Lucentis, and Eylea in a clinical trial. The study found all three drugs to be safe and effective for treating most people with DME. Patients who started the trial with 20/40 or better vision experienced similar improvements in vision no matter which of the three drugs they were given. However, patients who started the trial with 20/50 or worse vision had greater improvements in vision with Eylea.

Most people require monthly anti-VEGF injections for the first six months of treatment. Thereafter, injections are needed less often: typically three to four during the second six months of treatment, about four during the second year of treatment, two in the third year, one in the fourth year, and none in the fifth year. Dilated eye exams may be needed less often as the disease stabilizes.

Avastin, Lucentis, and Eylea vary in cost and in how often they need to be injected, so patients may wish to discuss these issues with an eye care professional.

The retina of a person with diabetic retinopathy and DME, as viewed by optical coherence tomography (OCT). The two images were taken before (Top) and after anti-VEGF treatment (Bottom). The dip in the retina is the fovea, a region of the macula where vision is normally at its sharpest. Note the swelling of the macula and elevation of the fovea before treatment.

Focal/grid macular laser surgery. In focal/grid macular laser surgery, a few to hundreds of small laser burns are made to leaking blood vessels in areas of edema near the center of the macula. Laser burns for DME slow the leakage of fluid, reducing swelling in the retina. The procedure is usually completed in one session, but some people may need more than one treatment. Focal/grid laser is sometimes applied before anti-VEGF injections, sometimes on the same day or a few days after an anti-VEGF injection, and sometimes only when DME fails to improve adequately after six months of anti-VEGF therapy.

Corticosteroids. Corticosteroids, either injected or implanted into the eye, may be used alone or in combination with other drugs or laser surgery to treat DME. The Ozurdex (dexamethasone) implant is for short-term use, while the Iluvien (fluocinolone acetonide) implant is longer lasting. Both are biodegradable and release a sustained dose of corticosteroids to suppress DME. Corticosteroid use in the eye increases the risk of cataract and glaucoma. DME patients who use corticosteroids should be monitored for increased pressure in the eye and glaucoma.

How is proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) treated?

For decades, PDR has been treated with scatter laser surgery, sometimes called panretinal laser surgery or panretinal photocoagulation. Treatment involves making 1,000 to 2,000 tiny laser burns in areas of the retina away from the macula. These laser burns are intended to cause abnormal blood vessels to shrink. Although treatment can be completed in one session, two or more sessions are sometimes required. While it can preserve central vision, scatter laser surgery may cause some loss of side (peripheral), color, and night vision. Scatter laser surgery works best before new, fragile blood vessels have started to bleed. Recent studies have shown that anti-VEGF treatment not only is effective for treating DME, but is also effective for slowing progression of diabetic retinopathy, including PDR, so anti-VEGF is increasingly used as a first-line treatment for PDR.

What is a vitrectomy?

A vitrectomy is the surgical removal of the vitreous gel in the center of the eye. The procedure is used to treat severe bleeding into the vitreous, and is performed under local or general anesthesia. Ports (temporary water-tight openings) are placed in the eye to allow the surgeon to insert and remove instruments, such as a tiny light or a small vacuum called a vitrector. A clear salt solution is gently pumped into the eye through one of the ports to maintain eye pressure during surgery and to replace the removed vitreous. The same instruments used during vitrectomy also may be used to remove scar tissue or to repair a detached retina.

Vitrectomy may be performed as an outpatient procedure or as an inpatient procedure, usually requiring a single overnight stay in the hospital. After treatment, the eye may be covered with a patch for days to weeks and may be red and sore. Drops may be applied to the eye to reduce inflammation and the risk of infection. If both eyes require vitrectomy, the second eye usually will be treated after the first eye has recovered.

What if treatment doesn’t improve vision?

An eye care professional can help locate and make referrals to low vision and rehabilitation services and suggest devices that may help make the most of remaining vision. Many community organizations and agencies offer information about low vision counseling, training, and other special services for people with visual impairment. A nearby school of medicine or optometry also may provide low vision and rehabilitation services.

Glaucoma

More Information

Facts About Glaucoma

This information was developed by the National Eye Institute to help patients and their families search for general information about glaucoma. An eye care professional who has examined the patient’s eyes and is familiar with his or her medical history is the best person to answer specific questions.

Glaucoma Defined

What is Glaucoma?

Glaucoma is a group of diseases that damage the eye’s optic nerve and can result in vision loss and blindness. However, with early detection and treatment, you can often protect your eyes against serious vision loss.

The optic nerve

The optic nerve is a bundle of more than 1 million nerve fibers. It connects the retina to the brain. (See diagram above.) The retina is the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye. A healthy optic nerve is necessary for good vision.

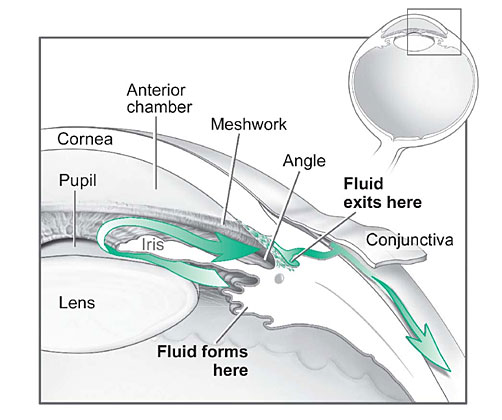

How does the optic nerve get damaged by open-angle glaucoma?

Several large studies have shown that eye pressure is a major risk factor for optic nerve damage. In the front of the eye is a space called the anterior chamber. A clear fluid flows continuously in and out of the chamber and nourishes nearby tissues. The fluid leaves the chamber at the open angle where the cornea and iris meet. (See diagram below.) When the fluid reaches the angle, it flows through a spongy meshwork, like a drain, and leaves the eye.

In open-angle glaucoma, even though the drainage angle is “open”, the fluid passes too slowly through the meshwork drain. Since the fluid builds up, the pressure inside the eye rises to a level that may damage the optic nerve. When the optic nerve is damaged from increased pressure, open-angle glaucoma-and vision loss—may result. That’s why controlling pressure inside the eye is important.

Another risk factor for optic nerve damage relates to blood pressure. Thus, it is important to also make sure that your blood pressure is at a proper level for your body by working with your medical doctor.

Fluid pathway is shown in teal.

Can I develop glaucoma if I have increased eye pressure?

Not necessarily. Not every person with increased eye pressure will develop glaucoma. Some people can tolerate higher levels of eye pressure better than others. Also, a certain level of eye pressure may be high for one person but normal for another.

Whether you develop glaucoma depends on the level of pressure your optic nerve can tolerate without being damaged. This level is different for each person. That’s why a comprehensive dilated eye exam is very important. It can help your eye care professional determine what level of eye pressure is normal for you.

Can I develop glaucoma without an increase in my eye pressure?

Yes. Glaucoma can develop without increased eye pressure. This form of glaucoma is called low-tension or normal-tension glaucoma. It is a type of open-angle glaucoma.

Who is at risk for open-angle glaucoma?

Anyone can develop glaucoma. Some people, listed below, are at higher risk than others:

- African Americans over age 40

- Everyone over age 60, especially Mexican Americans

- People with a family history of glaucoma

A comprehensive dilated eye exam can reveal more risk factors, such as high eye pressure, thinness of the cornea, and abnormal optic nerve anatomy. In some people with certain combinations of these high-risk factors, medicines in the form of eyedrops reduce the risk of developing glaucoma by about half.

Glaucoma Symptoms

At first, open-angle glaucoma has no symptoms. It causes no pain. Vision stays normal. Glaucoma can develop in one or both eyes.

Without treatment, people with glaucoma will slowly lose their peripheral (side) vision. As glaucoma remains untreated, people may miss objects to the side and out of the corner of their eye. They seem to be looking through a tunnel. Over time, straight-ahead (central) vision may decrease until no vision remains.

Normal Vision.

The same scene as viewed by a person with glaucoma.

How is glaucoma detected?

Glaucoma is detected through a comprehensive dilated eye exam that includes the following:

Visual acuity test. This eye chart test measures how well you see at various distances.

Visual field test. This test measures your peripheral (side vision). It helps your eye care professional tell if you have lost peripheral vision, a sign of glaucoma.

Dilated eye exam. In this exam, drops are placed in your eyes to widen, or dilate, the pupils. Your eye care professional uses a special magnifying lens to examine your retina and optic nerve for signs of damage and other eye problems. After the exam, your close-up vision may remain blurred for several hours.

Tonometry is the measurement of pressure inside the eye by using an instrument called a tonometer. Numbing drops may be applied to your eye for this test. A tonometer measures pressure inside the eye to detect glaucoma.

Pachymetry is the measurement of the thickness of your cornea. Your eye care professional applies a numbing drop to your eye and uses an ultrasonic wave instrument to measure the thickness of your cornea.

Can glaucoma be cured?

No. There is no cure for glaucoma. Vision lost from the disease cannot be restored.

Glaucoma Treatments

Immediate treatment for early-stage, open-angle glaucoma can delay progression of the disease. That’s why early diagnosis is very important.

Glaucoma treatments include medicines, laser trabeculoplasty, conventional surgery, or a combination of any of these. While these treatments may save remaining vision, they do not improve sight already lost from glaucoma.

Medicines. Medicines, in the form of eyedrops or pills, are the most common early treatment for glaucoma. Taken regularly, these eyedrops lower eye pressure. Some medicines cause the eye to make less fluid. Others lower pressure by helping fluid drain from the eye.

Before you begin glaucoma treatment, tell your eye care professional about other medicines and supplements that you are taking. Sometimes the drops can interfere with the way other medicines work.

Glaucoma medicines need to be taken regularly as directed by your eye care professional. Most people have no problems. However, some medicines can cause headaches or other side effects. For example, drops may cause stinging, burning, and redness in the eyes.

Many medicines are available to treat glaucoma. If you have problems with one medicine, tell your eye care professional. Treatment with a different dose or a new medicine may be possible.

Because glaucoma often has no symptoms, people may be tempted to stop taking, or may forget to take, their medicine. You need to use the drops or pills as long as they help control your eye pressure. Regular use is very important.

A tonometer measures pressure inside the eye to detect glaucoma.

Make sure your eye care professional shows you how to put the drops into your eye. For tips on using your glaucoma eyedrops, see the inside back cover of this booklet.

Laser trabeculoplasty. Laser trabeculoplasty helps fluid drain out of the eye. Your doctor may suggest this step at any time. In many cases, you will need to keep taking glaucoma medicines after this procedure.

Laser trabeculoplasty is performed in your doctor’s office or eye clinic. Before the surgery, numbing drops are applied to your eye. As you sit facing the laser machine, your doctor holds a special lens to your eye. A high-intensity beam of light is aimed through the lens and reflected onto the meshwork inside your eye. You may see flashes of bright green or red light. The laser makes several evenly spaced burns that stretch the drainage holes in the meshwork. This allows the fluid to drain better.

Like any surgery, laser surgery can cause side effects, such as inflammation. Your doctor may give you some drops to take home for any soreness or inflammation inside the eye. You will need to make several follow-up visits to have your eye pressure and eye monitored.

If you have glaucoma in both eyes, usually only one eye will be treated at a time. Laser treatments for each eye will be scheduled several days to several weeks apart.

Studies show that laser surgery can be very good at reducing the pressure in some patients. However, its effects can wear off over time. Your doctor may suggest further treatment.

Conventional surgery. Conventional surgery makes a new opening for the fluid to leave the eye. (See diagram on the next page.) Your doctor may suggest this treatment at any time. Conventional surgery often is done after medicines and laser surgery have failed to control pressure.

Conventional surgery, called trabeculectomy, is performed in an operating room. Before the surgery, you are given medicine to help you relax. Your doctor makes small injections around the eye to numb it. A small piece of tissue is removed to create a new channel for the fluid to drain from the eye. This fluid will drain between the eye tissue layers and create a blister-like “filtration bleb.”

For several weeks after the surgery, you must put drops in the eye to fight infection and inflammation. These drops will be different from those you may have been using before surgery.

Conventional surgery is performed on one eye at a time. Usually the operations are four to six weeks apart.

Conventional surgery is about 60 to 80 percent effective at lowering eye pressure. If the new drainage opening narrows, a second operation may be needed. Conventional surgery works best if you have not had previous eye surgery, such as a cataract operation.

Sometimes after conventional surgery, your vision may not be as good as it was before conventional surgery. Conventional surgery can cause side effects, including cataract, problems with the cornea, inflammation, infection inside the eye, or low eye pressure problems. If you have any of these problems, tell your doctor so a treatment plan can be developed.

What are some other forms of glaucoma and how are they treated?

Open-angle glaucoma is the most common form. Some people have other types of the disease.

In low-tension or normal-tension glaucoma, optic nerve damage and narrowed side vision occur in people with normal eye pressure. Lowering eye pressure at least 30 percent through medicines slows the disease in some people. Glaucoma may worsen in others despite low pressures.

A comprehensive medical history is important to identify other potential risk factors, such as low blood pressure, that contribute to low-tension glaucoma. If no risk factors are identified, the treatment options for low-tension glaucoma are the same as for open-angle glaucoma.

In angle-closure glaucoma, the fluid at the front of the eye cannot drain through the angle and leave the eye. The angle gets blocked by part of the iris. People with this type of glaucoma may have a sudden increase in eye pressure. Symptoms include severe pain and nausea, as well as redness of the eye and blurred vision. If you have these symptoms, you need to seek treatment immediately. This is a medical emergency. If your doctor is unavailable, go to the nearest hospital or clinic. Without treatment to restore the flow of fluid, the eye can become blind. Usually, prompt laser surgery and medicines can clear the blockage, lower eye pressure, and protect vision.

In congenital glaucoma, children are born with a defect in the angle of the eye that slows the normal drainage of fluid. These children usually have obvious symptoms, such as cloudy eyes, sensitivity to light, and excessive tearing. Conventional surgery typically is the suggested treatment, because medicines are not effective and can cause more serious side effects in infants and be difficult to administer. Surgery is safe and effective. If surgery is done promptly, these children usually have an excellent chance of having good vision.

Conventional surgery makes a new opening for the fluid to leave the eye.

Secondary glaucomas can develop as complications of other medical conditions. For example, a severe form of glaucoma is called neovascular glaucoma, and can be a result from poorly controlled diabetes or high blood pressure. Other types of glaucoma sometimes occur with cataract, certain eye tumors, or when the eye is inflamed or irritated by a condition called uveitis. Sometimes glaucoma develops after other eye surgeries or serious eye injuries. Steroid drugs used to treat eye inflammations and other diseases can trigger glaucoma in some people. There are two eye conditions known to cause secondary forms of glaucoma.

Pigmentary glaucoma occurs when pigment from the iris sheds off and blocks the meshwork, slowing fluid drainage.

Pseudoexfoliation glaucoma occurs when extra material is produced and shed off internal eye structures and blocks the meshwork, again slowing fluid drainage.

Depending on the cause of these secondary glaucomas, treatment includes medicines, laser surgery, or conventional or other glaucoma surgery.

What research is being done?

Through studies in the laboratory and with patients, NEI is seeking better ways to detect, treat, and prevent vision loss in people with glaucoma. For example, researchers have discovered genes that could help explain how glaucoma damages the eye.

NEI also is supporting studies to learn more about who is likely to get glaucoma, when to treat people who have increased eye pressure, and which treatment to use first.

What You Can Do

If you are being treated for glaucoma, be sure to take your glaucoma medicine every day. See your eye care professional regularly.

You also can help protect the vision of family members and friends who may be at high risk for glaucoma-African Americans over age 40; everyone over age 60, especially Mexican Americans; and people with a family history of the disease. Encourage them to have a comprehensive dilated eye exam at least once every two years. Remember that lowering eye pressure in the early stages of glaucoma slows progression of the disease and helps save vision.

Medicare covers an annual comprehensive dilated eye exam for some people at high risk for glaucoma. These people include those with diabetes, those with a family history of glaucoma, and African Americans age 50 and older.

What should I ask my eye care professional?

You can protect yourself against vision loss by working in partnership with your eye care professional. Ask questions and get the information you need to take care of yourself and your family.

What are some questions to ask?

About my eye disease or disorder…

- What is my diagnosis?

- What caused my condition?

- Can my condition be treated?

- How will this condition affect my vision now and in the future?

- Should I watch for any particular symptoms and notify you if they occur?

- Should I make any lifestyle changes?

About my treatment…

- What is the treatment for my condition?

- When will the treatment start and how long will it last?

- What are the benefits of this treatment and how successful is it?

- What are the risks and side effects associated with this treatment?

- Are there foods, medicines, or activities I should avoid while I’m on this treatment?

- If my treatment includes taking medicine, what should I do if I miss a dose?

- Are other treatments available?

About my tests…

- What kinds of tests will I have?

- What can I expect to find out from these tests?

- When will I know the results?

- Do I have to do anything special to prepare for any of the tests?

- Do these tests have any side effects or risks?

- Will I need more tests later?

Other suggestions

- If you don’t understand your eye care professional’s responses, ask questions until you do understand.

- Take notes or get a friend or family member to take notes for you. Or, bring a tape recorder to help you remember the discussion.

- Ask your eye care professional to write down his or her instructions to you.

- Ask your eye care professional for printed material about your condition.

- If you still have trouble understanding your eye care professional’s answers, ask where you can go for more information.

- Other members of your healthcare team, such as nurses and pharmacists, can be good sources of information. Talk to them, too.

Today, patients take an active role in their health care. Be an active patient about your eye care.

Loss of Vision

If you have lost some sight from glaucoma, ask your eye care professional about low vision services and devices that may help you make the most of your remaining vision. Ask for a referral to a specialist in low vision. Many community organizations and agencies offer information about low vision counseling, training, and other special services for people with visual impairments.

How should I use my glaucoma eyedrops?

If eyedrops have been prescribed for treating your glaucoma, you need to use them properly, as instructed by your eye care professional. Proper use of your glaucoma medication can improve the medicine’s effectiveness and reduce your risk of side effects.

To properly apply your eyedrops, follow these steps:

- Wash your hands.

- Hold the bottle upside down.

- Tilt your head back.

- Hold the bottle in one hand and place it as close as possible to the eye.

- With the other hand, pull down your lower eyelid. This forms a pocket.

- Place the prescribed number of drops into the lower eyelid pocket. If you are using more than one eyedrop, be sure to wait at least 5 minutes before applying the second eyedrop.

- Close your eye OR press the lower lid lightly with your finger for at least 1 minute. Either of these steps keeps the drops in the eye and helps prevent the drops from draining into the tear duct, which can increase your risk of side effects.

The National Eye Institute (NEI) is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and is the Federal government’s lead agency for vision research that leads to sight-saving treatments and plays a key role in reducing visual impairment and blindness.

Myopia

Refractive errors include nearsightedness and farsightedness, eye conditions that are very common. Most people have one or more of them. Refractive errors can usually be corrected with eyeglasses or contact lens.

More Information

Facts About Refractive Errors

This information was developed by the National Eye Institute to help patients and their families search for general information about refractive errors. An eye care professional who has examined the patient’s eyes and is familiar with his or her medical history is the best person to answer specific questions.

Refractive Errors Defined

What are refractive errors?

Refractive errors occur when the shape of the eye prevents light from focusing directly on the retina. The length of the eyeball (longer or shorter), changes in the shape of the cornea, or aging of the lens can cause refractive errors.

What is refraction?

Refraction is the bending of light as it passes through one object to another. Vision occurs when light rays are bent (refracted) as they pass through the cornea and the lens. The light is then focused on the retina. The retina converts the light-rays into messages that are sent through the optic nerve to the brain. The brain interprets these messages into the images we see.

Frequently Asked Questions about Refractive Errors

What are the different types of refractive errors?

The most common types of refractive errors are myopia, hyperopia, presbyopia, and astigmatism.

Myopia (nearsightedness) is a condition where objects up close appear clearly, while objects far away appear blurry. With myopia, light comes to focus in front of the retina instead of on the retina.

Hyperopia (farsightedness) is a common type of refractive error where distant objects may be seen more clearly than objects that are near. However, people experience hyperopia differently. Some people may not notice any problems with their vision, especially when they are young. For people with significant hyperopia, vision can be blurry for objects at any distance, near or far.

Astigmatism is a condition in which the eye does not focus light evenly onto the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye. This can cause images to appear blurry and stretched out.

Presbyopia is an age-related condition in which the ability to focus up close becomes more difficult. As the eye ages, the lens can no longer change shape enough to allow the eye to focus close objects clearly.

Risk Factors

Who is at risk for refractive errors?

Presbyopia affects most adults over age 35. Other refractive errors can affect both children and adults. Individuals that have parents with certain refractive errors may be more likely to get one or more refractive errors.

Symptoms and Detection

What are the signs and symptoms of refractive errors?

Blurred vision is the most common symptom of refractive errors. Other symptoms may include:

- Double vision

- Haziness

- Glare or halos around bright lights

- Squinting

- Headaches

- Eye strain

How are refractive errors diagnosed?

An eye care professional can diagnose refractive errors during a comprehensive dilated eye examination. People with a refractive error often visit their eye care professional with complaints of visual discomfort or blurred vision. However, some people don’t know they aren’t seeing as clearly as they could.

Treatment

How are refractive errors treated?

Refractive errors can be corrected with eyeglasses, contact lenses, or surgery.

Eyeglasses are the simplest and safest way to correct refractive errors. Your eye care professional can prescribe appropriate lenses to correct your refractive error and give you optimal vision.

Contact Lenses work by becoming the first refractive surface for light rays entering the eye, causing a more precise refraction or focus. In many cases, contact lenses provide clearer vision, a wider field of vision, and greater comfort. They are a safe and effective option if fitted and used properly. It is very important to wash your hands and clean your lenses as instructed in order to reduce the risk of infection.

If you have certain eye conditions you may not be able to wear contact lenses. Discuss this with your eye care professional.

Refractive Surgery aims to change the shape of the cornea permanently. This change in eye shape restores the focusing power of the eye by allowing the light rays to focus precisely on the retina for improved vision. There are many types of refractive surgeries. Your eye care professional can help you decide if surgery is an option for you.